With continuous allegations of chemical weapons use in Syria and opposing sides accusing each other, it has become difficult to to establish culpability. However, it remains possible to analyze the situation with scientific evidences and logical reasoning.

By Adrien Morin

The latest suspected chemical attack in Syria occurred on 7 April 2018 in the city of Douma, killing more than 40 people. This attack is another entry on the list of alleged chemical attacks carried out by the Syrian government since 2012. It led to a major military response from the US, France and the UK, who carried out airstrikes on Syrian government installations (chemical plants and military bases).

The history of the Syrian chemical weapons program

The use of chemical and biological weapons in war is prohibited under the 1925 Geneva Protocol. In addition, the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) aimed to “eliminate an entire category of weapons of mass destruction by prohibiting the development, production, acquisition, stockpiling, retention, transfer or use of chemical weapons by States Parties.” Legally bound by the Geneva Protocol, Syria only joined the CWC in late 2013, amid international pressure on the Assad regime to put an end to the use and stockpiling of chemical weapons in the country. The Syrian regime consequently started the destruction of its chemical weapons stockpiles under the supervision of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) and with the help of the US Army (in charge of transporting the chemical agents out of Syria and destroying them in cooperation with other international partners).

It is unclear how Syria acquired chemical weapons in the first place. In his 2007 book, ‘War of Nerves,’ Jonathan B. Tucker explained that Syria first put its hands on chemical weapons between the late 1960s to early 1970s, with the assistance of Egypt. Egyptian president Anwar Sadat and his Syrian counterpart Hafez al-Assad had equipped their forces with chemical weapons on the occasion of a 1973 surprise attack against Israel, which was “plotted to avenge their nations’ humiliating defeat in the 1967 Six-Day War.” According to the American expert, Cairo sold chemical weapons to Damascus for $6 million, including “sarin-filled artillery shells, Scud missile warheads, and spray tanks for tactical aircraft.” After a three-week military confrontation, the Israel Defense Forces were able to repeal the attack. The Egyptian and Syrian forces, in fear of retaliation, restrained from using chemical weapons against Israel.

A 2013 report from the Congressional Research Service citing American intelligence sources, argued that Syria started developing its own chemical weapons program in the late 1970s and early 1980s. At that occasion, it “is likely to have procured equipment and precursor chemicals from private companies in Western Europe.” On 23 July 2012, Syrian Foreign Ministry spokesman Jihad Makdissi acknowledged for the first time that his country possessed chemical weapons. Finally, a 2013 declassified report from French intelligence estimated that the Syrian military chemical arsenal exceeded 1,000 tons of military-grade chemical agents and precursors (the chemical agents necessary to create the military-grade agents):

- several hundred tons of mustard gas;

- several dozen tons of VX;

- several hundred tons of sarin gas.

How do these chemical weapons work?

Chemical agents have different properties and effects on the human body. Chlorine and sarin have been the two most widely used chemicals in the Syrian conflict. Sulfur mustard (mustard gas) has also been detected several times, with strong suspicions that the Islamic State was behind these attacks. Finally, Agent 15 was allegedly involved in an attack in December 2012, but without reliable evidence to support the claim.

Chlorine

Chlorine is a very commonly manufactured chemical used to bleach paper and cloth. It is also used in other commercial purposes such as treating water and making pesticides. However, chlorine can also be weaponized. It can be turned into a liquid form for storage and then sprayed through various delivery systems (warheads, spray-tanks etc.). Once released, chlorine turns into an odorous gas which can come into contact with moist tissues such as the eyes, throat and lungs. It damages tissues and affects the respiratory system, resulting in severe injuries or even death by asphyxia. Chlorine is thus considered a choking agent.

Chlorine has been used as a weapon on the battlefield since World War I; more specifically, the Battle of Ypres when German troops released the gas from barrels and relied on the wind to poison French troops opposing them. Compared to many other chemical weapons, chlorine is relatively “easy” to manufacture and acquire, and could potentially be used by nonstate actors.

Sarin

Sarin takes its name from the German scientists who helped develop it in the late 1930s (Schrader, Ambros, Ritter and von der Linde). It is a nerve agent (affecting the human nervous system) that is not naturally present in the environment. Sarin is a clear, colorless, tasteless and very volatile liquid, that can easily evaporate and be vaporized in the environment (like a gas). It is usually weaponized using a spraying system that can be included in different delivery systems (warheads, spray-tanks etc.). Sarin affects the function of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, disturbing the nervous system’s ability to regulate muscles contractions. Sarin is therefore an extremely potent nerve agent that causes death by asphyxia by effectively paralyzing the muscles involved in regulating the respiratory system.

Sarin is extremely difficult to manufacture. It involves precursors that are both very difficult to acquire (because they are banned according to the terms of the CWC) and dangerous to handle. Manufacturing military-grade sarin thus requires the ability to acquire rare (and banned) chemical agents and the possession of very high quality and complex equipment (to handle very corrosive materials and store them). In addition, it necessitates the presence of highly skilled chemical experts to oversee this entire manufacturing and storage process. All of this does not even take into account the difficulties in manufacturing or acquiring delivery systems that can efficiently spray sarin on a targeted area.

Because of the difficulties in acquiring or manufacturing sarin, and then weaponizing it, it is highly probable that its use on the battlefield comes from state actors. The only proven exception to date is the 1994-1995 sarin terrorist attacks in Japan, carried out by the doomsday cult Aum Shinrikyo. The 1995 Tokyo subway attack, in particular, cost the lives of 12 while severely injuring 54 and moderately affecting 980. It also pushed 5,000 to seek medical assistance. However, casualties could have been much higher had the attackers used a pure (military-grade) form of sarin. Instead, the sarin was then only 35% pure. Aum Shinrikyo’s chemist, Tsuchiya, had proven in the past that he could manufacture 90% pure sarin but only in small quantity. In any case, the Japanese cult, even with significant resources and skills, was unable to use military-grade sarin for its terrorist attack. Therefore, Aum Shinrikyo’s sarin attack is the exception as opposed to the rule, and it remains highly improbable that nonstate actors could be behind sarin chemical attacks alone.

VX

Although no evidence supports the thesis of the use of VX in the Syrian conflict, it is still a chemical agent that was allegedly stockpiled in large amounts by the Syrian government. VX is the most potent of all the nerve agents. It is less volatile than sarin, making it harder to spray on a battleground and more persistent (it decays slowly) in the environment. Just like sarin, VX impacts the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, leading to an overstimulation of the muscles and eventually to the collapse of the respiratory system, resulting in death by asphyxia.

Due to its incredibly high toxicity and corrosivity, VX is even harder to store (and attach to delivery systems) than sarin. Besides access denial (contaminating an area for several days), the military purpose of VX is limited. It has been more commonly used in assassination operations (any skin contact with liquid VX is technically lethal) like the one that targeted North Korean leader Kim Jong-un’s half-brother, Kim Jong-nam, in 2017.

Sulfur Mustard

Sulfur mustard (or mustard gas) takes its name from the smell that results from its dissemination in an area (although it can sometimes be odorless). It has no other purpose than being used as a weapon. Sulfur mustard is stored in liquid form and sprayed on the battlefield. It is a blistering agent (it causes blistering of the skin and mucous membranes upon contact) that damages DNA, causing the dysfunction of the cells involved in the respiratory system and resulting in severe injuries or death by asphyxia.

Sulfur mustard is relatively simple to manufacture and, according to the OPCW, “can therefore be a ‘first choice’ when a country decides to build up a capacity for chemical warfare.” It could potentially be developed by nonstate actors (as long as they can find a way to get ahold of the chemical precursors that are difficult to acquire) but its potency would be dependent of the purity of the product and, by extension, of the skills and equipment of the individuals involved in the manufacturing process. The Islamic State, for instance, is suspected to be behind sulfur mustard attacks in Syria, although it is unclear if it produced the poisonous gas or acquired it through other channels.

Agent 15

Agent 15 (whose actual existence is debatable) is an agent considered to be chemically almost identical to BZ (3-Quinuclidinyl Benzilate). BZ is a psychotomimetic (or psychochemical) incapacitating agent (much less toxic than nerve or blistering agents) whose effects include for example hallucinations, agitation, blurred vision and hypertension, and can be lethal in high doses. It can be used as a weapon and sprayed on the battleground through different delivery systems but its military purpose remains limited (aside from incapacitating individuals without necessarily killing them) with little evidence of previous use in armed conflicts.

Agent 15 was allegedly used in a 2012 chemical attack in Homs, but some analysts have denied the allegation, arguing that the agent was never actually produced by Iraq (the country which would have provided Syria with the chemical agent in the first place), a claim that was confirmed by a CIA report.

How can we determine whether a chemical attack occurred?

Aside from graphic pictures and videos showcasing suffocating individuals and field-reports describing symptoms correlated with an exposure to chemical agents, there are scientific methods used to determine whether chemical weapons were used. The OPCW is the internationally recognized body in charge of investigations of alleged use (IAU), which according to the organization, “involves sampling of environmental and biomedical samples and their analysis in an area where chemical weapons were allegedly used.” IAUs have primarily been implemented in Syria in recent years. These missions are carried out by analytical chemists who are trained by the OPCW prior to conducting field missions.

In sum, the OPCW uses reliable methods and equipment to determine the presence, in a given area, of chemical agents suggesting a past chemical attack. “False positives” (when a chemical compound is wrongly identified as a banned substance on the OCAD) are the biggest challenge to the reliability of the OPCW’s sampling and analysis operations, but they remain marginal overall. The biggest limitation to the OPCW activities is the impossibility to carry out operations because of a dangerous environment and the refusal of the host country (or other countries during negotiations at the United Nations) to let OPCW agents operate on its territory.

Who is behind chemical attacks in Syria?

Determining who is behind a chemical attack is the trickiest part. Since the beginning of the conflict in Syria, neither pro-government forces nor rebel groups claimed responsibility for the use of chemical weapons and, on the contrary, both sides have repeatedly accused each other of doing so. Scientific processes like the ones used by the OPCW can prove the use of chemical weapons in a given area but they cannot determine who carried out the chemical attack. This lack of certainty pushed different actors to formulate different hypotheses following an alleged chemical attack, disregarding scientific evidence and blurring the line between empirical analyses and speculations (or even conspiracy theories).

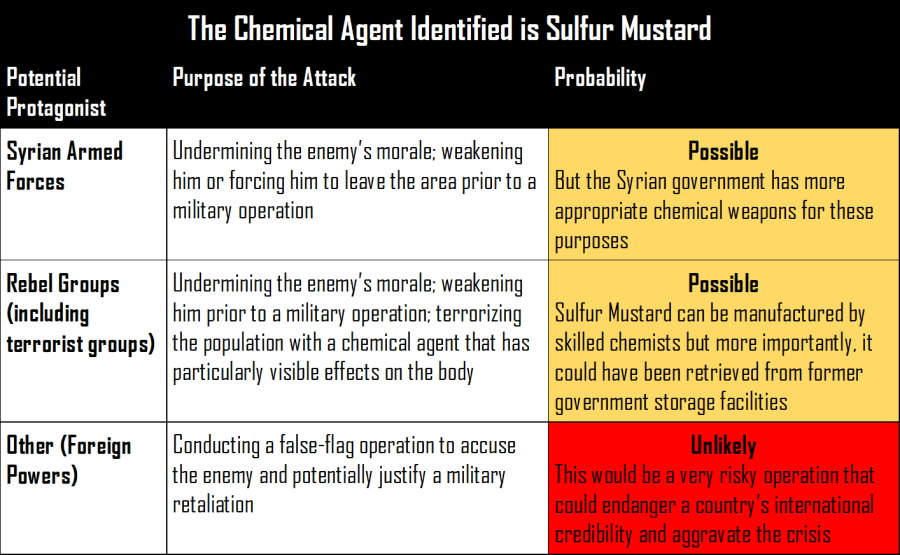

This section proposes a basic methodological tool to assess, in terms of probability, who could be the instigator of a chemical attack. The key elements to keep in mind are the following:

- Nerve agents are extremely difficult to acquire, manufacture, handle and weaponize. Their use in the event of a chemical attack is very unlikely to come from anyone other than a state actor.

- Syria had stockpiled significant amounts of mustard gas, sarin and VX prior to the civil war.

- The Syrian government is the only confirmed actor to have had (and most likely still have) possession of chemical weapons and to have sufficient capabilities to manufacture complex chemical agents (in chemical plants).

- Chlorine is the easiest chemical agent to weaponize (though less potent than nerve or blistering agents).

Now, let us consider the hypothesis of a chemical attack in a rebel-held territory or in an area with a large presence of opponents (both civilians or armed groups) to the Assad regime (the most common scenario observed throughout the Syrian civil war).

The categorizations presented above are purely informational and do not constitute evidences of the responsibility of one actor or another. These evidences can be acquired by identifying the delivery systems used to spread the chemical weapons in a given area. However, given the lack of on-site media coverage and the challenges of accessing these regions in conflict, it is often very difficult to formally establish culpability.

Many have argued that there are too many flaws in the accusations against the Syrian regime’s alleged use of chemical weapons because Bashar al-Assad would simply have too much to lose by illegally resorting to them. Yet, these arguments usually ignore two major factors:

- Chemical weapons are very efficient tactical tools, especially in the context of a civil war. They have a strong psychological effect on the populations targeted as they spread the fear of an invisible lethal threat that could be anywhere. More importantly, chemical weapons weaken the enemy and clear an area prior to a military intervention, without necessarily destroying all the infrastructure. This is especially important in order to regain territorial control, an objective actively pursued by the Assad regime in Syria.

- The Assad regime benefits from Russian (and Iranian) support and Moscow has not changed its position despite repeated alleged uses of chemical weapons in Syria. The Syrian leader does not have to fear for a foreign military intervention (aside from occasional airstrikes) in his country as long as Russian troops will be stationed there.

Highly politicized speculations about alleged use of chemical weapons in Syria are negatively impacting the public debate whereas scientific methods exist to expose more reliable evidences. These, however, remain difficult to obtain today because of the many obstacles to the smooth conduct of the OPCW operations on the ground, in Syria. Formally designating a culprit after a chemical attack is also a major challenge, but again, a good understanding of chemical weapons as well as every party’s strategic and tactical interests can allow us to draw some logical inferences, on a case by case basis. At the age of mass information and social media, it is our governments and media groups’ responsibilities to stop blurring the lines with politically motivated statements, and rather promote hard evidences and logical reasoning.

Note: this article only seeks to provide an understanding of chemical weapons in the context of the Syrian civil war. It does not suggest or support political or military responses to the crisis, such as the airstrikes conducted by the US, the UK and France outside of any form of international consensus.

Cover Picture: pile of gas masks that have been assembled and tested, © State Library Victoria Collections / flickr